Alternative Shelter

Context

In Portland, the “village” model has emerged as a typology for addressing homelessness that recognizes the logic of the communities that people experiencing homelessness are creating for themselves while endeavoring to provide a safer and more impactful response than encampments. Villages in Portland are understood to mean transitional housing communities consisting of individual seeping “pods” for individuals, with shared kitchen, bathroom, and gathering facilities. Portland is home to the country's first and longest running village, Dignity Village, which grew out of protest in 2000 through the concerted efforts of houseless activists. With this community providing a guidepost, the village movement finally began to gain traction in response to a declaration of a state of emergency on housing and homelessness in the City of Portland in late 2015. Since that time, the Center for Public Interest Design has worked with a range of stakeholders to support the creation of several villages, guided by the expertise of those with lived experience with homelessness.

In addition to the creation of villages, this work has resulted in dozens of community workshops, several high-profile exhibits on the work, and a growing network of hundreds of volunteers from the design and construction communities that have contributed to this effort. The villages themselves have evolved over a short period of a few years to include utilities, wrap-around services, new strategies for site development, and policy changes at the city and state level to support this work. New efforts are underway to study the impact of villages to better advise groups in Portland and across the country hoping to replicate similar models for addressing homelessness in their communities. At the same time, the CPID's alternative shelter research acknowledges that the solution to homelessness is permanent housing. This research is also grounded in a belief that villages represent only one possibility on a vast spectrum between sleeping on the street and having permanent housing, and that the investment and infrastructure to support villages and alternative shelters can be reimagined to actually incentivize the creation of permanent housing. To that end, we have been working with students to explore both new models for better affordable housing and villages, and entirely new visions for alternative shelter that promise to open up innovative design and research possibilities in this work going forward.

Location

Portland Metro Region

Kenton Women’s Village 1.0

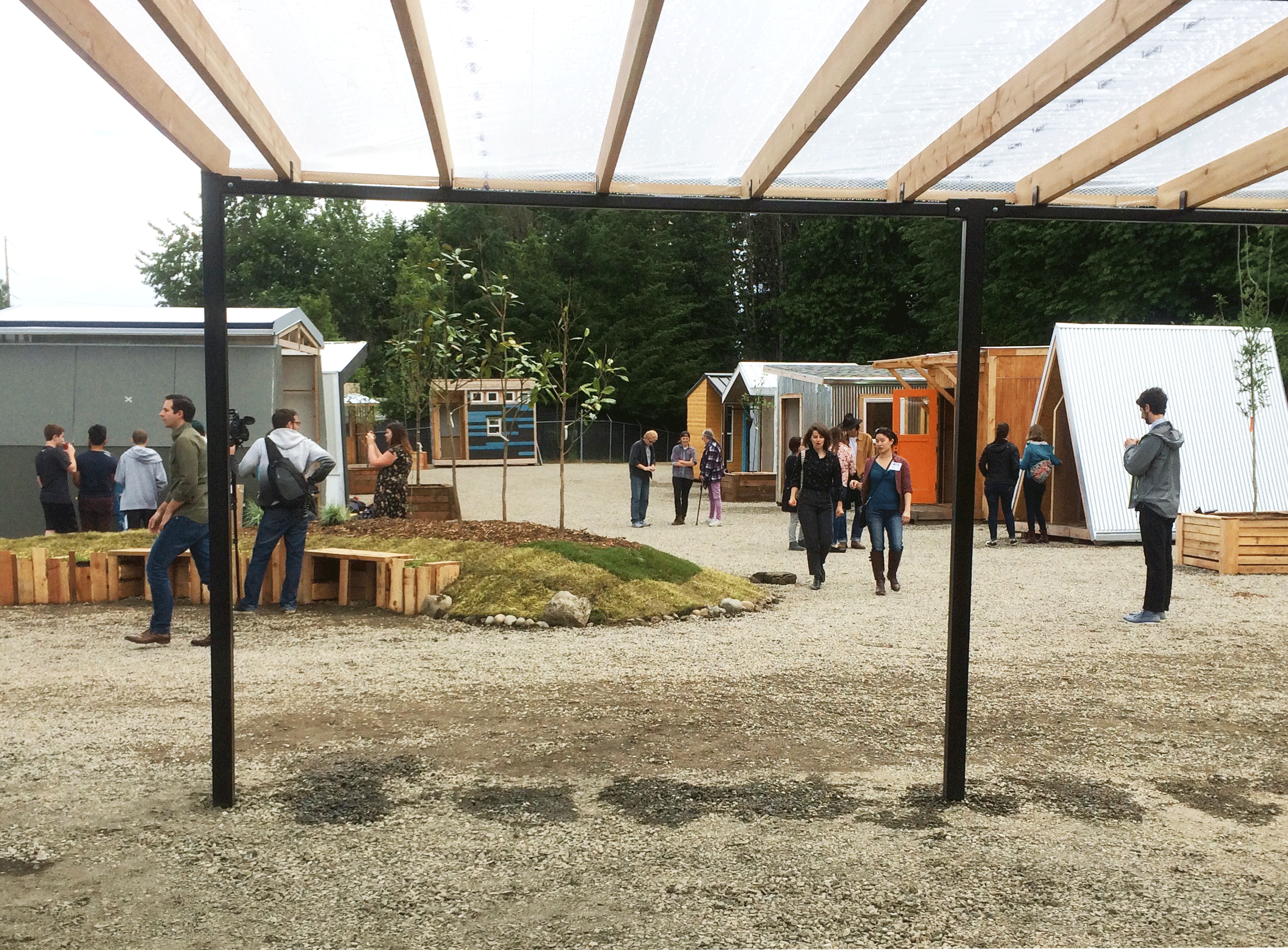

The Kenton Women’s Village is a transitional housing community in North Portland for houseless women. The project grew out of the POD Initiative, an effort led by the CPID with partners at City Repair and the Village Coalition in the fall of 2016 to explore how Portland’s architecture community could respond to the city’s state of emergency on homelessness. This initiative resulted in 14 tiny houses called sleeping pods designed and built by teams of architects, PSU students, and volunteers.

While an available site in the Kenton neighborhood was identified when the pods were completed in December 2016, the partners embarking on this effort did not want to simply “drop” a village into a community that was not prepared to welcome the village into their neighborhood. The Kenton Women’s Village would provide immediate housing to women that needed it, while serving as a pilot project that could be replicated in other neighborhoods throughout Portland. With this in mind, the organizing team promised to give the neighborhood an opportunity to work with the project partners and vote on whether to allow the village to move forward in their neighborhood before any action was taken. After an intensive community engagement process led by the CPID and PSU School of Architecture students, the Kenton neighborhood took a vote on March 8, 2017, that resulted in a decisive victory with a margin of over 2 to 1 in favor.The village opened in June of 2017. One year later when the village asked for an extension to remain in place for another year while a permanent site was identified, the vote was nearly unanimous with a staggering 119 to 3 vote in favor of keeping the village in Kenton.

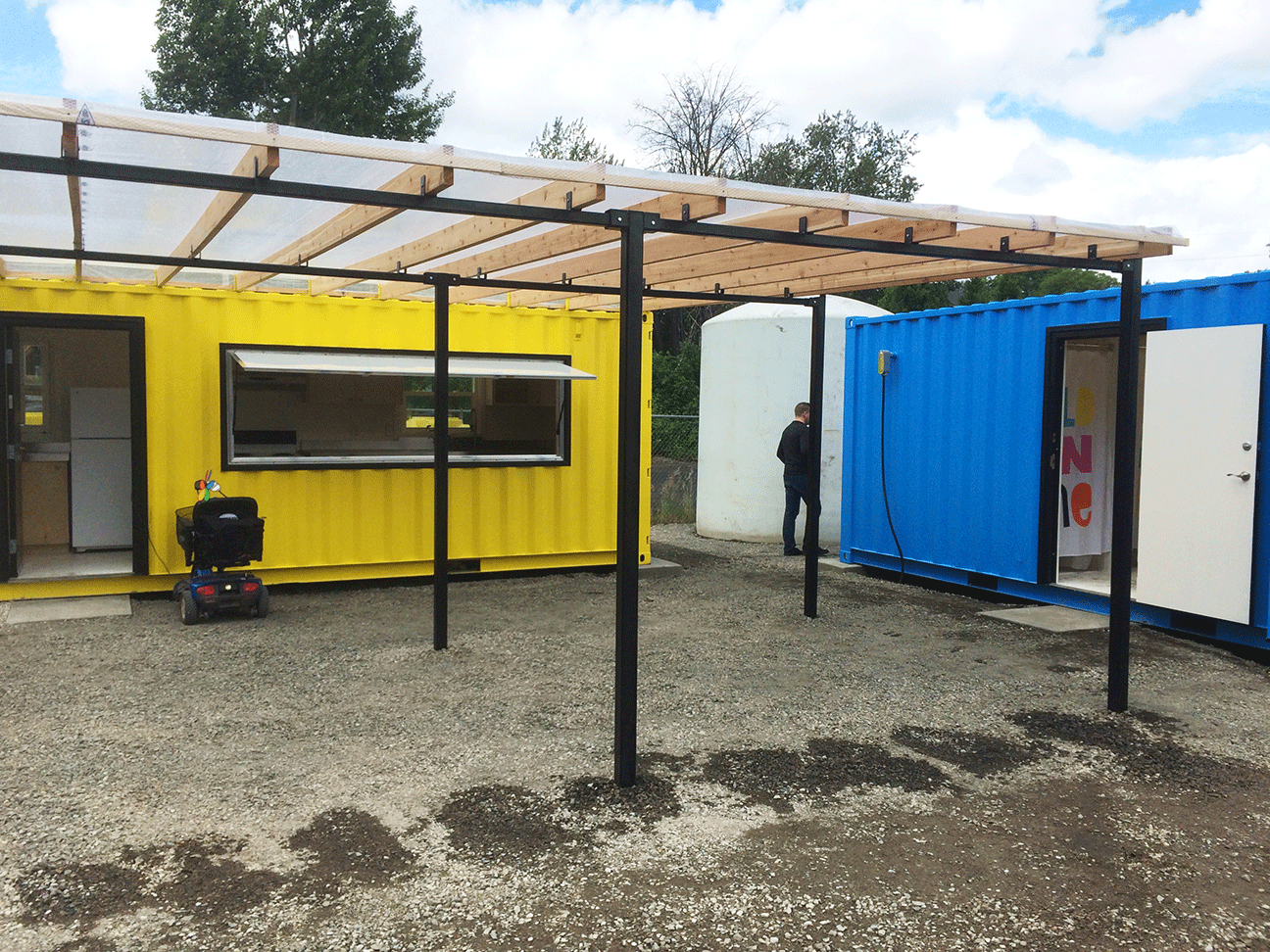

While the village model is informed by incredible communities and villages that houseless Portlanders have created for themselves, the Kenton Women’s Village represents an entirely new step in the village evolution - the first city-sponsored, fully supported village created through a participatory process. The village is managed by Catholic Charities with 2 full-time staff dedicated to the village. In its original iteration as a pilot project (Kenton Women’s Village 1.0) of 14 pods, every woman had a tiny house (sleeping pod) to herself that was created through the POD Initiative. There was a shared kitchen facility made from a bright yellow shipping container with a concession door that opened onto a covered dining and gathering space. This area was enclosed on a second side with a blue shipping container hosting toilets, showers, and sinks. While electricity was available on site, there was no access to water or sewage lines, so water was delivered to a 6,000 gallon tank and captured in gray water storage tanks.

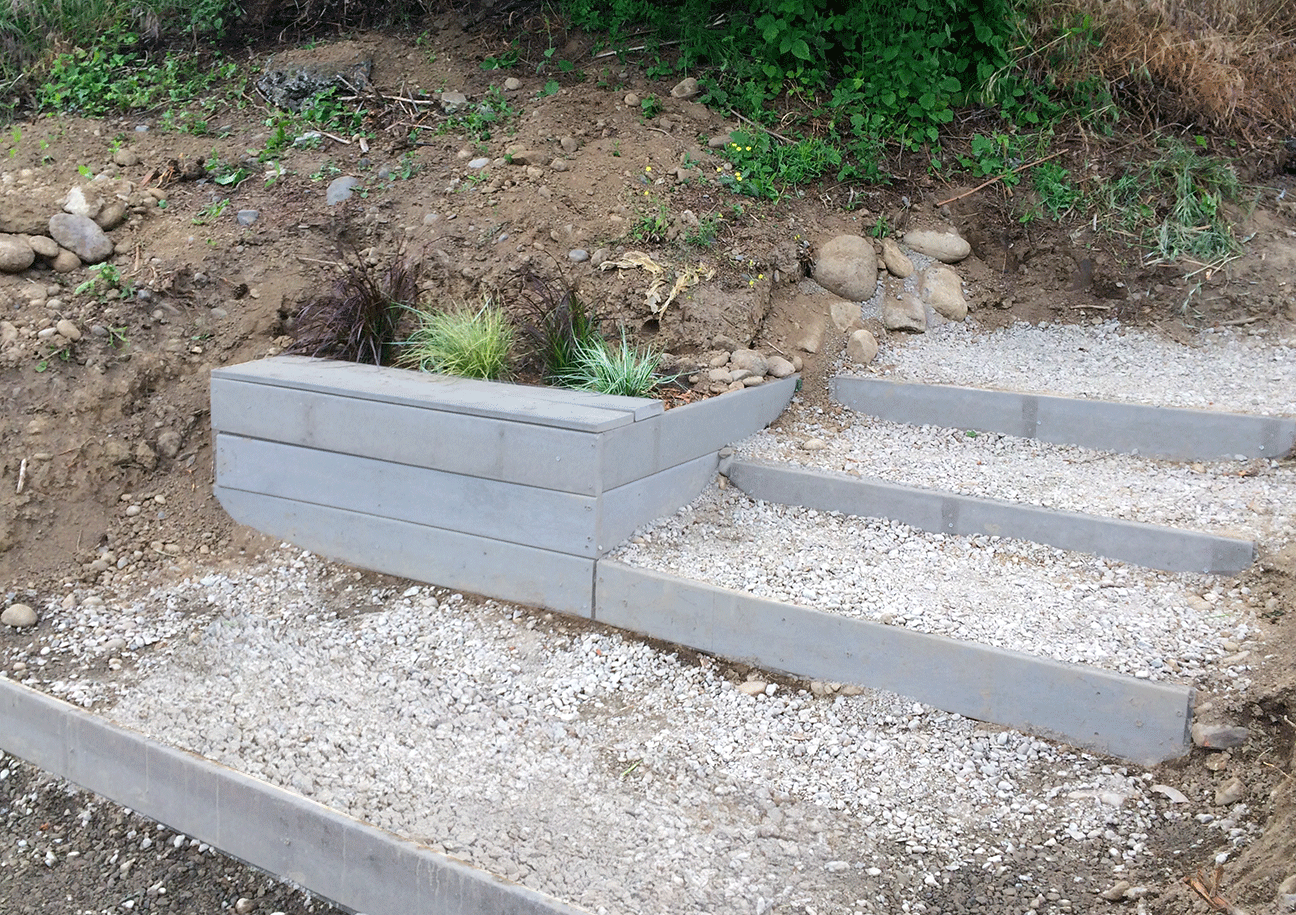

Students in the 2017 Public Interest Design seminar at PSU (Arch 433/533) designed and built site features aimed at placemaking. Partnering with City Repair, the students worked with dozens of volunteers over several days to create grassy berms creating a threshold that divides public and private areas of the site, steps embedded in a hillside that form a path from the village to transportation and the park, planter boxes to contain trees among the pods and create a community garden, and wooden screens adhered to chain link fencing for privacy and identity.

In its first 16 months in operation on the original site, Kenton Women’s Village transitioned 23 women into permanent housing. The success of this pilot project has resulted in several new villages in the region, and a permanent home for the Kenton Women’s Village (2.0) with improved structures, utilities, and amenities.

Kenton Women’s Village 2.0

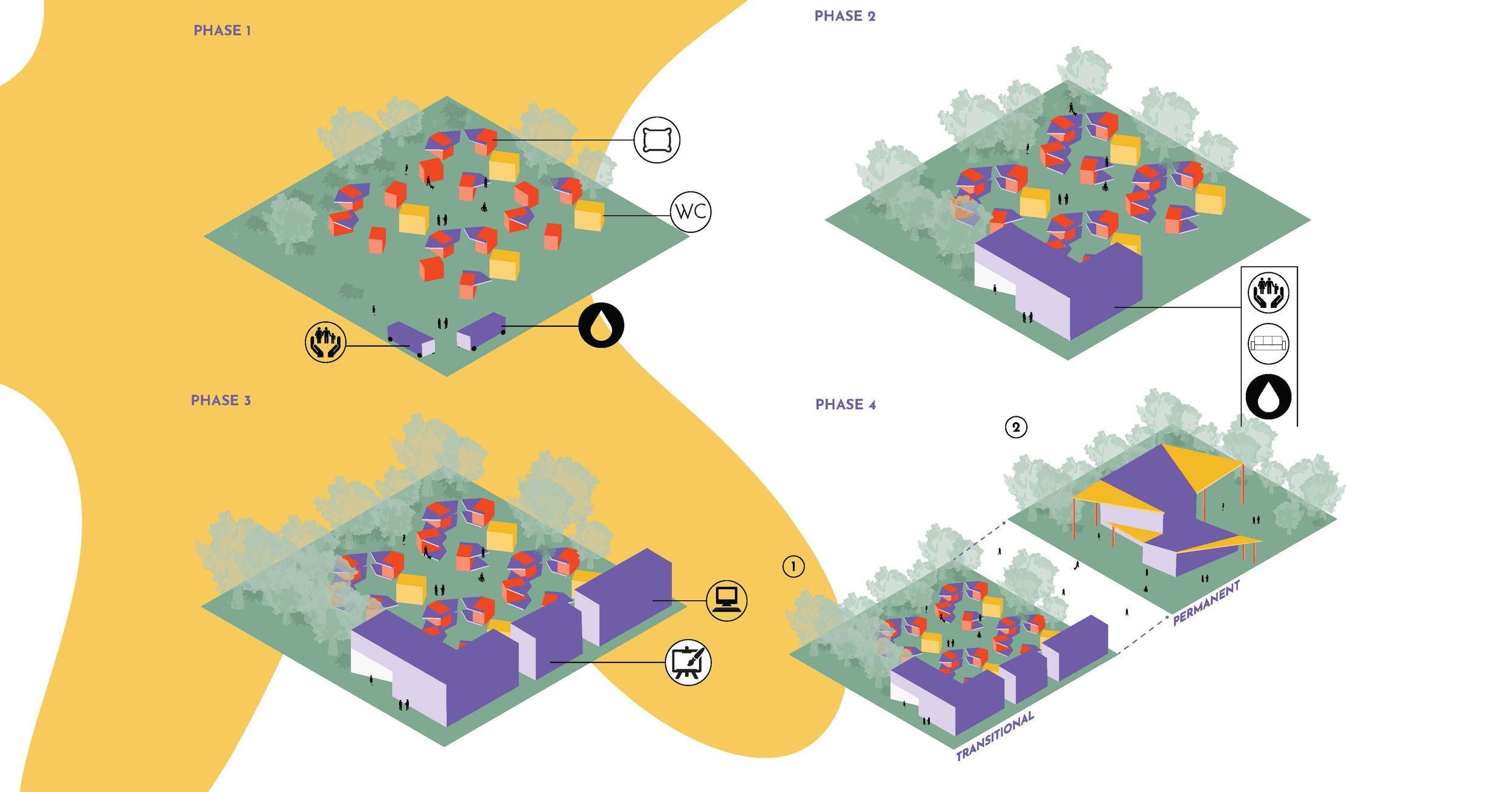

As a result of the success of the Kenton Women's Village during its phase as a pilot project, the program received an ongoing commitment of support from project partners at Catholic Charities and the City’s Joint Office of Homeless Services. A new site for an improved and more permanent village was identified within just a block of the previous village site, allowing the village to maintain its close relationship with neighborhood organizations and services in the Kenton neighborhood.

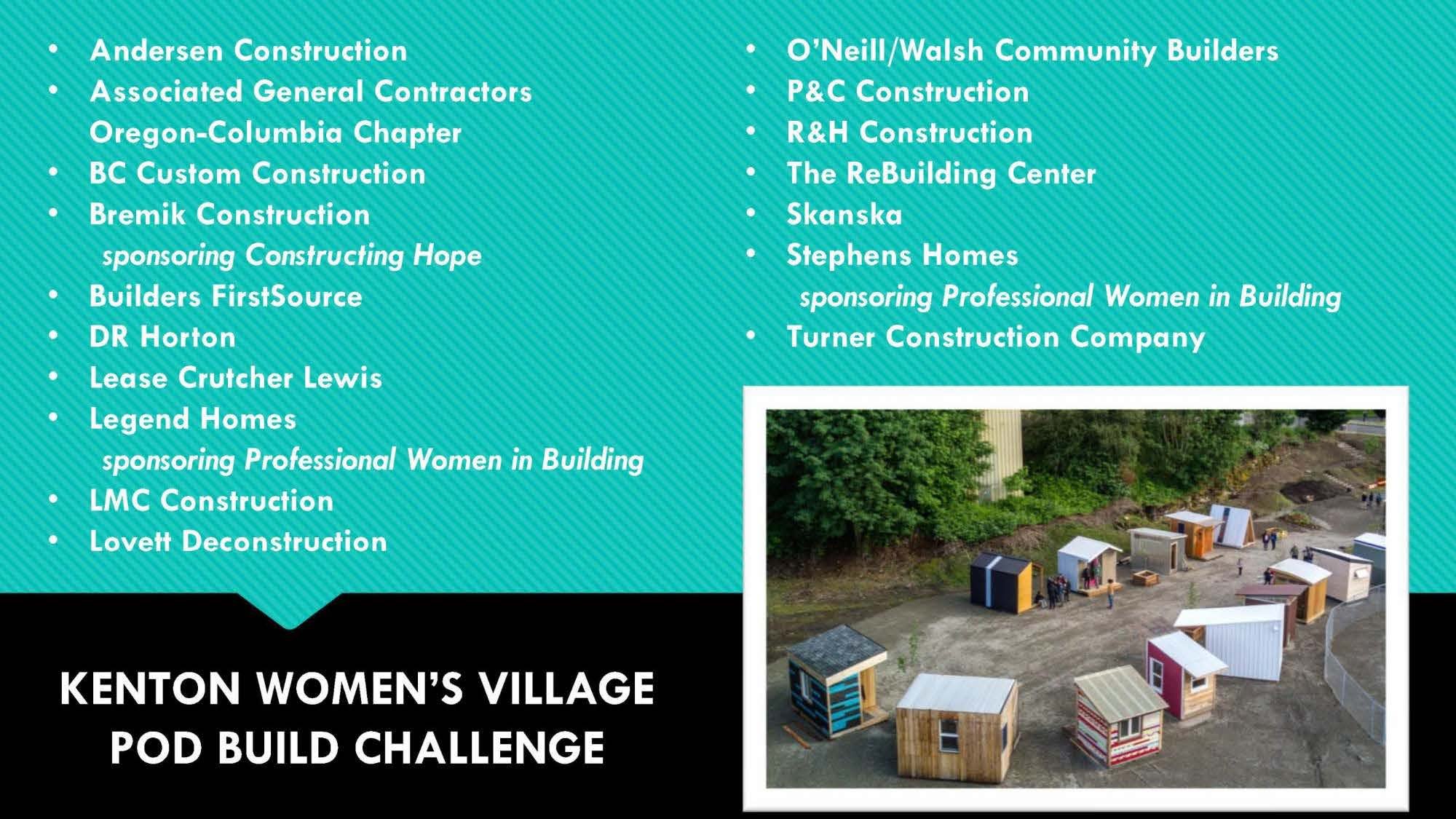

With the opportunity to bring upgraded utilities, infrastructure, and building accommodations to the site, the CPID and partners conducted rigorous post-occupancy evaluation research with residents, staff, and service providers to determine the needs for the new village. As the planning of the site developed through a participatory process, the number of tiny houses /pods (and thus, women served) increased from 14 to 20. In order to build the new pods and replace older prototypes that were less successful, the CPID and partners worked with the construction community through the launch of the POD Build Challenge.

The challenge invited local construction firms to build a pod based on three designs that were evaluated by stakeholders to be the most suitable for the needs of the village and most loved by their residents. One of the three, the Pop-Out Pod, was created by CPID faculty with School of Architecture students. Construction firms were encouraged to be creative, think sustainably, and advance the designs through use of material, storage, and amenities. The result was 21 beautiful pods are all equipped with full electricity to support lighting, outlets, and built-in radiant heating panels, setting a new standard for pods in the area. With such enthusiastic participation from the building community, the village received more pods than were able to be used at that site, and an additional 8 pods were donated to expand the CPID designed Clackamas County Veterans Village.

In addition to supporting village planning and coordination with partners from SRG Partnership, LMC Construction, Catholic Charities, Portland HomeBuilders Foundation, and Andersen Construction, CPID Faculty Fellows Todd Ferry and Margarette Leite also designed the village’s new common facility. With a need to be highly affordable, movable (should the village ever need to relocate), and low to the ground, the team designed the building out of several reclaimed shipping containers. The result is a compelling 680 square foot building that features three toilets, two showers, a laundry facility, a kitchen, and living room.

Clackamas County Veterans Village

The Clackamas County Veterans Village is a transitional shelter community for veterans. The village is the result of a collaboration between Clackamas County, Catholic Charities, Communitecture, City Repair, the Village Coalition, Lease Crutcher Lewis, Portland State University School of Architecture, the Center for Public Interest Design, partners in the City of Portland and Multnomah County, and others.

The Clackamas County Veterans Village opened with 15 sleeping pods and has begun adding more toward the goal of 30 total (the village is currently at 26 pods). The initial 15 pods were built using hundreds of wooden trusses that originally formed the 2017 Treeline Stage at the Pickathon music festival, which was designed and built by PSU architecture students and faculty in the Diversion Design-Build Studio course.

In designing the residential areas of the village, PSU researchers arranged the sleeping pods into clusters, following recommendations developed by a graduate architecture master’s student whose thesis had focused on designing veterans housing. Shared facilities include a large kitchen, bathrooms and showers, laundry, a TV lounge and meeting space where veterans can talk with their caseworkers and other service providers. Communitecture, the project’s architect of record, based the tiny dwellings on an original design by SRG Partnership known as the “S.A.F.E. Pod,” each of which utilizes 21 trusses. The sleeping pods come with a bed, interior storage space, operable windows and a porch with a built-in seat. Some of the pods have been adapted to meet ADA standards, and all pods have full electricity, built in lighting, and radiant heat.

In October 2018, the veterans moved into their new community and began receiving individualized services, including skills-based training. In partnership with Clackamas County, village operators Do Good Multnomah provide veterans with primary medical & dental care, mental health counseling, substance abuse counseling, social services, housing service assistance, and employment assistance & training.

Agape Village

Agape Village is located at the base of Kelly Butte on the property of the Portland Central Nazarene Church. The site was previously a quarry and remained largely vacant until the church leadership and nonprofit partners decided to build a self-governed village to serve the houseless community. The idea for a transitional housing village was conceived by the church as a humanitarian response to the influx of people experiencing houselessness and seeking shelter on their grounds and in the surrounding area. Completed in late 2019, Agape Village hosts 15 sleeping pods, with nonprofit Cascadia Clusters leading the development. As part of Cascadia Clusters’ model, the pods were built by members of the houseless community (and potential future village residents) who earn an income and learn the construction trade through the process. Another one of the group’s innovations is the creation of a portable “Maker Village” which is being used to house the builders and provide a tool shop at the site. Once Agape Village was completed, the Maker Village was relocated to help seed another future village in Portland.

Students in PSU's Graduate Certificate in Public Interest Design program Center for Public Interest Design and architecture studios have contributed to design efforts at Agape Village. While not the primary organizer or coordinator of the village, faculty and students supported organizing efforts of Agape Village through placemaking on site, the design of a new pod type (The Condo Pod), and site planning and design.

The site plan for Agape Village was designed based on comprehensive engagement with village stakeholders. The community members wanted a large open area for a communal gathering space and future amenities like a kitchen, bathroom, and showers. The horseshoe shaped configuration allows for a strengthened sense of community, clear sight lines across the site for security, and a large open space. The site design also takes into account required 10’ spacing between pods, accessibility for emergency/construction vehicles, safety for residents, wind and noise reduction, and preservation of views.

The “Condo Pod” was designed specifically for the needs of Agape Village and provided the basis for the 15 built pods on site. Led by CPID student Melissa Mulder-Wright, the design features an upper loft, ample storage space, floor-level amenities, flexibility of use, and an attached ‘garage’ at the rear of the pod (under the loft). This design was further developed by Cascadia Clusters to include heating, lighting, and outlets that are fully solar-powered.

What If…

What if a night market model were applied to houseless services? What if transit stops transformed into micro-shelters at night? What if existing wall space could be activated to provide shelter for people experiencing homelessness?

In response to an increasing number of people experiencing homelessness in Portland and in other cities around the country, many communities are looking toward alternative shelter typologies that might be able to respond to the urgency of the problem while working toward more permanent solutions. In recent years, the village model has developed as a leading alternative to traditional shelters. Villages represent a crucial point on the spectrum between the street and permanent housing, but it is worth remembering that there are innumerous other points along that same spectrum that might also contribute to addressing homelessness.

Students in Todd Ferry's design studios have explored new visions for an expanded field of alternative shelter typologies, including new approaches to the design of villages. This work builds upon a growing body of work at the School of Architecture, Center for Public Interest Design, and Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative intended to demonstrate the power of design to serve traditionally underserved populations. While permanent housing for all remains the ultimate goal, this work endeavors to offer alternative shelter approaches in the interest of supporting our friends and community members experiencing homelessness.

This work has been exhibited in several places in the interest of promoting public dialogue around addressing homelessness, including at Portland’s City Hall in Oregon and the Anchorage Museum in Alaska.

AfroVillage

The AfroVillage is more than physical space. It is a movement rooted in the vision of Laquida Landford, a Portland community member and activist. The movement focuses on addressing the needs of our most vulnerable population, unhoused individuals, with a focus on racial disparities and inequalities. The AfroVillage movement acknowledges the realities that: current villages and alternative shelter models offer a lot of promise but do not adequately serve the BIPOC communities that experience homelessness at disproportionately high rates; Safe spaces that specifically serve the Black community (both housed and unhoused individuals) are critically needed to allow for healing and gathering, as systemic racism has pushed the African American community further away from Portland’s city center; and that in addition to creating a central hub for people experiencing homelessness that utilizes the village model in more culturally specific ways, integrated outreach efforts that bring amenities such as hygiene stations, fresh food, and educational programming to Black community members where they are is also essential.

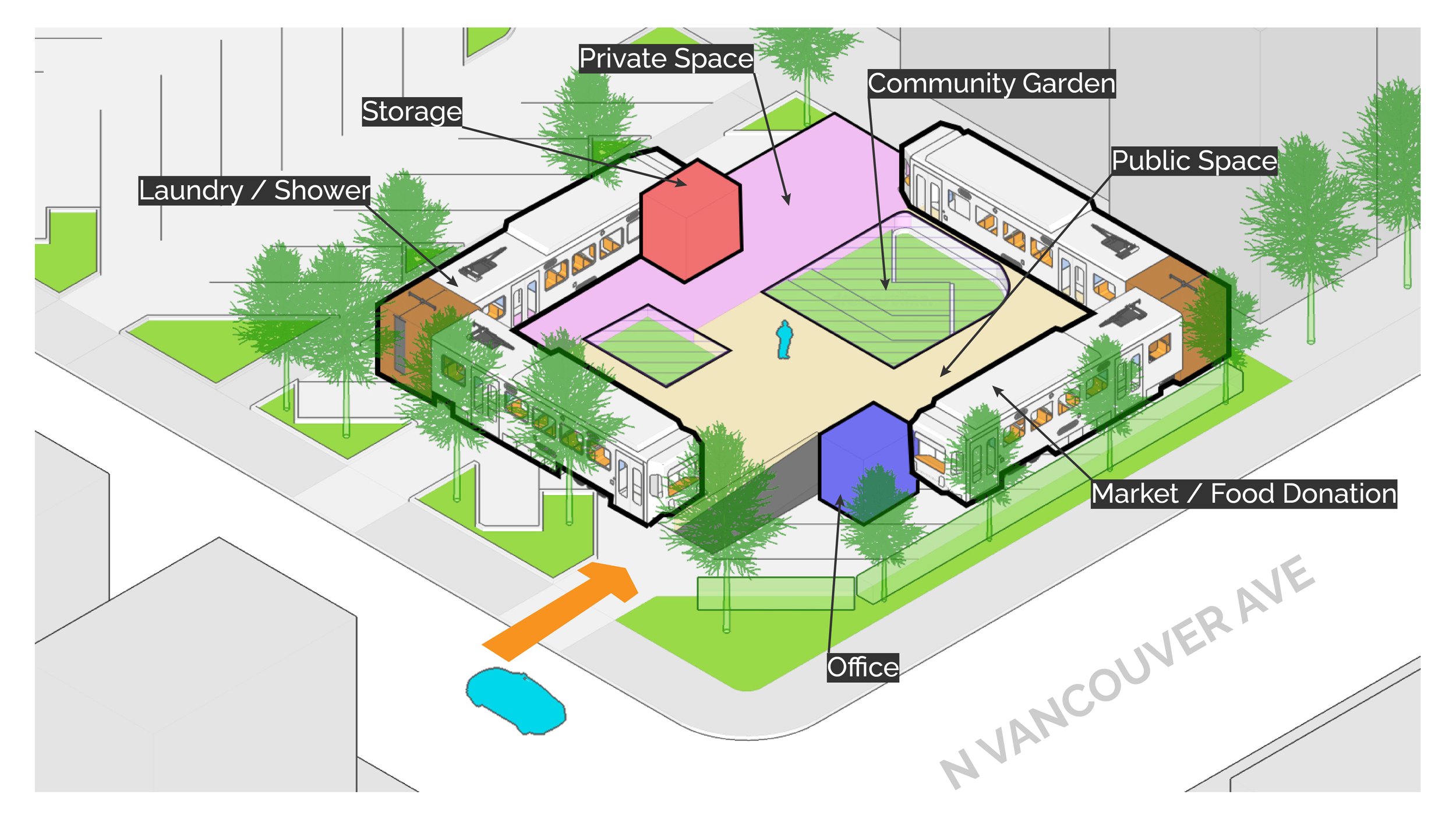

The Center for Public Interest Design has been supporting the AfroVillage mission with research, design, and community outreach assistance in design studios and in through the CPID Fellows program. AfroVillage Homebase has grown out of the MAX Reuse Design Challenge organized by the Center for Public Interest Design, Trimet, and the Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. The AfroVillage team submitted a design proposing the reuse of three trains to support the mission of AfroVillage. The trains aim to fulfill the demand of more equitable, just and accessible basic services while providing safe and healing spaces for Portland’s most vulnerable community. This proposal was awarded the People’s Choice Award in the competition and has already received significant grant funding toward turning this vision into a reality.

Currently, CPID is one of the partners supporting AfroVillage leadership in site feasibility studies for a permanent AfroVillage Hub, are offering coordination for the AfroVillage Homebase, and have been exploring mobile placemaking proposals to meet the AfroVillage’s outreach goals. The AfroVillage Homebase explores an entirely new vision for what alternative shelter might look like in the region with an emphasis on ultimately transferring land and housing ownership into the hands of the black community.

Pods (Design-Build)

Faculty at the CPID have worked with students on the design and construction of several sleeping pod prototypes. Students have been tasked with understanding the City from the perspective of individuals experiencing homelessness, designing solutions at the city, neighborhood, village, and individual human scale. The individual scale is brought to life with an alternative shelter proposal. All of the conditions that make a piece of architecture a truly meaningful space for its inhabitants (or not) are found within the program of the pod. Students ranging from those first testing architecture in PSU's Architecture Summer Immersion Program to students in their penultimate undergraduate design studio have undertaken pod and village design. In several of the advanced studios, this has resulted in prototype sleeping pods that the students designed and built in the course of just 10 weeks.

The first major pod design was the Trot Pod. Responding to desires and issues that were discussed in a design charrette with houseless individuals and advocates, students settled on a design that aimed to include details such as a thoughtful division of space, storage systems, an abundance of light, multiple operable windows, and a porch. The design echoes the icon of a house with a gable roof, which is clad in black standing seam metal that wraps down along the walls as well. A translucent white polycarbonate window and skylight create a strip of diffused light in the pod that brightens both the bed area and table/desk nook. Copper piping and reclaimed wood interact to create shelves, table tops, hanging racks, and a foot rest. The pod takes advantage of the largest allowable footprint (8’x12’), which includes a 4’x4’ porch. The pod gets its name from both the studio’s proposed site for a village and concepts related to their aggregation and expansion. The pod is designed to work well independently, but also to work in a pair with a shared porch similar to a typology known as a dogtrot. This pod has housed several women at both the first and second Kenton Women’s Village.

The most recent pod design is the Pop-Out Pod. Students in Todd Ferry's studio conducted research and interviews to understand how existing pods were performing at Kenton Women’s Village and in other villages to determine how to make an ideal sleeping pod based on best practices. The pod that they developed was rooted in the qualities of comfort, storage, performance, and beauty. Pop-outs help break the feeling of being in a box, a crucial factor in such a small space. The pop-outs also provide important storage lacking in most other pod designs. Warmth and comfort were significant design drivers, so the pod uses 2x6 walls and 2x8 rafters for increased insulation when a heat source is unavailable (with 2x4 and radiant heating panels preferred). The design calls for an operable windows in the door, a fixed vertical window on the tall wall, and at least one large operable window within one of the pop-outs for ideal light and ventilation. The pod features a small covered porch, with recommendations for extending the porch with detached stairs that double as seating space. To promote a sense of separate space and to maximize room within the pod, much of the bed (twin bed size) is tucked into a nook created next to the porch. Finally, the original prototype built by students features a 3” C-Channel all the way around to accommodate straps used by forklifts during the moving of the pod to prevent damage. This pod has been replicated over 27 times, and is featured at the Kenton Women’s Village 2.0 and the Clackamas County Veterans Village. Additionally, the St. Johns Village which opened in 2021, utilized the Pop-Out Pod design as the sleeping pod for all 19 of the village’s units.

Exhibits & Community Dialogue

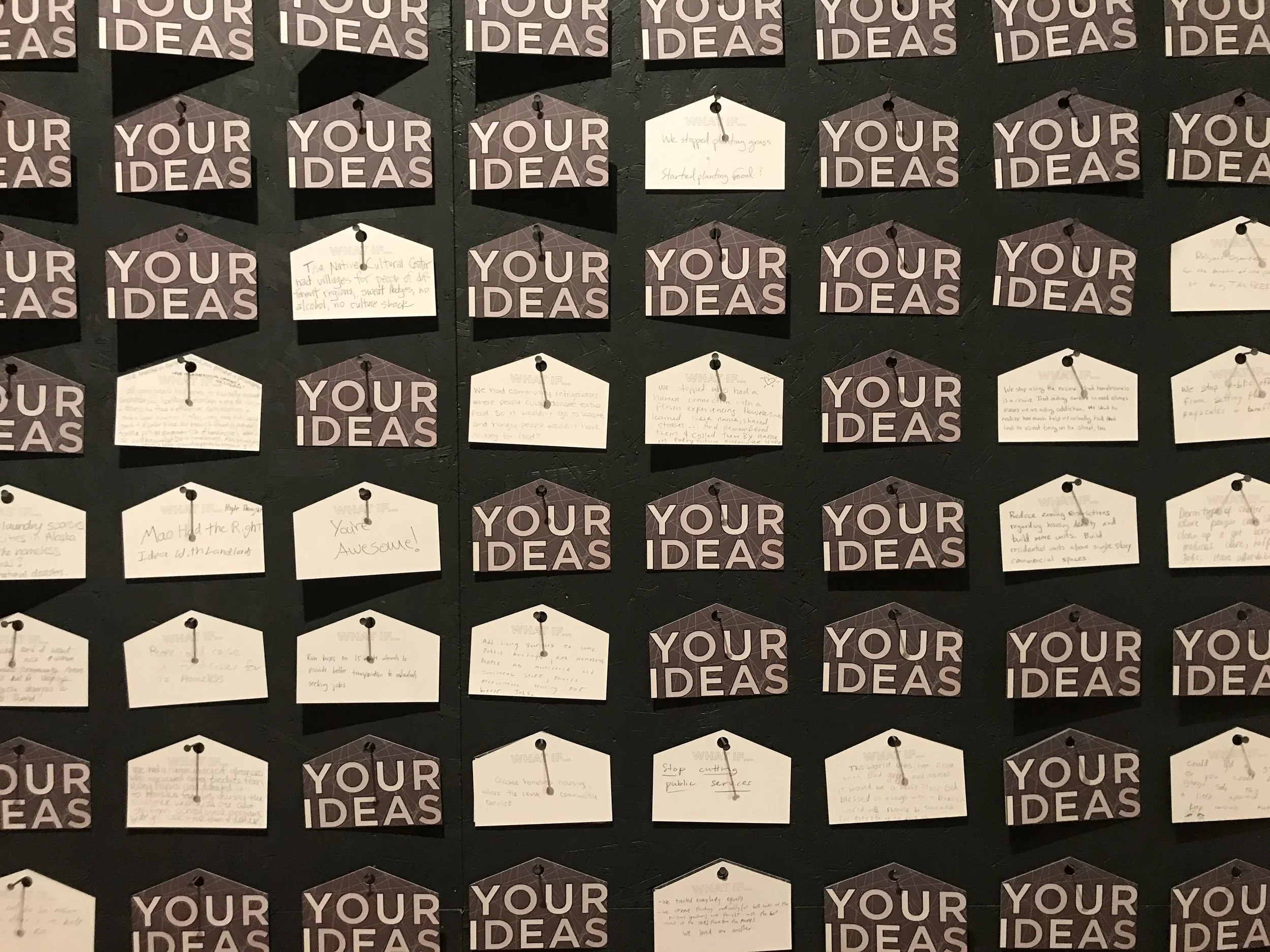

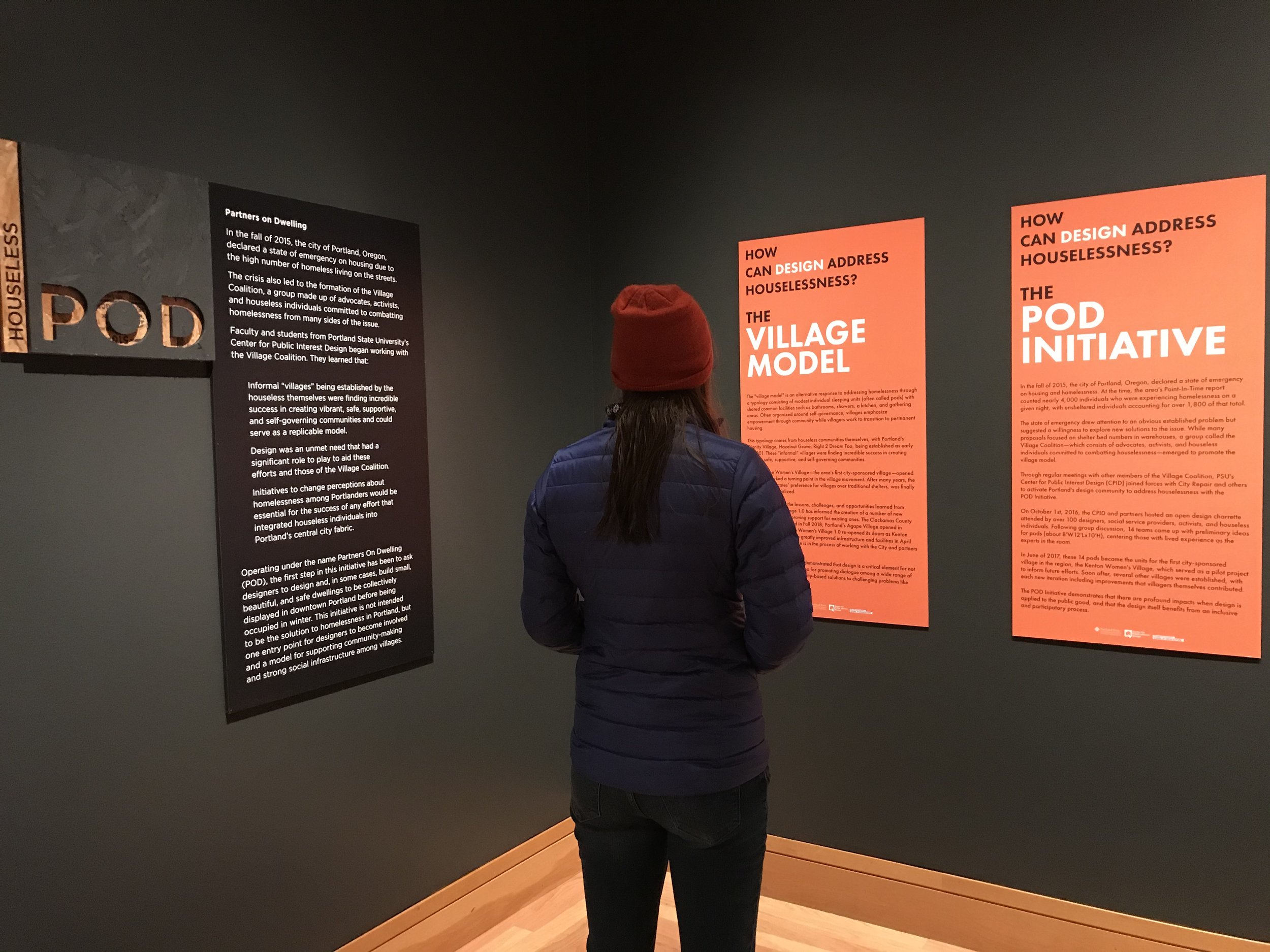

The work of the CPID promotes dialogue around the critical role that design can play to address homelessness and other pressing social and environmental issues. A recent exhibit at the Anchorage Museum coincided with workshops, lectures, and activities aimed at exploring alternative shelter options appropriate for Alaska’s unique culture and weather. The exhibit itself contained opportunities for visitors to reflect on their experiences with housing and homelessness, and local designers were invited to submit design for inclusion in the exhibit. Similarly, the [Plywood] POD Initiative at the Portland Art Museum invited local design firms to submit designs for plywood shelters that would be integrated into the exhibit, and one of the pods was built on the museum grounds in conjunction with other activities that invited community participation. In all cases, this work is rooted in the belief that design conversations need to be taken out of professional and academic circle and opened up to the larger community who are stakeholders in solving our collective social and environmental problems.

The Center for Public Interest Design partnered with PSU’s Homelessness Research & Action Collaborative (HRAC) and the Anchorage Museum on the exhibit Houseless, which explores ways in which design can contribute to solutions to houselessness. Design thinking helps break down complex problems and integrate new information and opinions, while acknowledging there is no one right answer. The Houseless project provides a space for awareness, education, and creative problem-solving around housing security in the Anchorage community and around the country. It supports individuals and communities in problem-solving together. Houseless brought together the National Building Museum’s exhibition Evicted, a presentation of the POD initiative from Portland State University’s Center for Public Interest Design (CPID), new visions for alternative shelter by the CPID and Anchorage designers through the What If? exhibit, and WE ARE ALL HOMELESS, a long-term project by designer Willie Baronet.

The [Plywood] POD Initiative asked architects and designers located in Portland and the Pacific Northwest to explore innovative new strategies which take advantage of plywood’s inherent properties toward beautiful and dignified transitional housing for the houseless. The 15 designs submitted fit the parameters of “sleeping pods,” which are designed to form a village in their aggregation with shared amenities like kitchens and showers. Participating teams submitted their designs, which were then reviewed by the POD Initiative organizers and representatives from people with lived experience in pod villages for inclusion in an exhibit at the Portland Art Museum. A pod designed by SERA Architects was chosen as the favorite pod by stakeholders, and was constructed at the museum before being moved to the Kenton Women's Village. The installation at the museum was designed by CPID faculty and students to highlight architecture's ability to make significant social impact, amplify the voices of houseless partners, emphasize the possibilities for plywood in itself, and create a design that could be reused to benefit the houseless community at the conclusion of the exhibit.